How Much Money Does Nys Give Its Counties

New York shifts more than of its Medicaid costs to local government than any other country.1 The 57 counties and New York Metropolis currently fund 12 pct of the overall program, or almost $8 billion a year.2

At that place is piddling dispute that requiring local governments to shoulder a big share of Medicaid costs—based not on ability to pay, just on celebrated patterns of need—is outmoded, dysfunctional and unfair. This system puts a unduly loftier brunt on localities with poorer residents and weaker tax bases. Even for wealthier counties, Medicaid is i of Albany'southward about onerous unfunded mandates—a major, ongoing expense over which local officials have no control.

Over the decades, land lawmakers have mitigated the burden by gradually lowering the counties' share of total spending, which was initially 25 percent. They capped the almanac growth of local payments in 2006, and froze the payments as of 2015. If non for those steps, local governments would exist paying $3.3 billion more per yr than they do at present.three

To date, nevertheless, the counties' longstanding plea for total relief from Medicaid costs has been stymied by the price tag: The local share now stands at $7.vi billion, including $5.iii billion from New York Metropolis and $ii.iii billion from the other 57 counties.4

Offsetting the loss of that much revenue would require either an enormous tax hike, deep cuts to health intendance spending or, most plausibly, a concerted, multi-year push button to squeeze efficiency from the Medicaid program.

Further complicating the task is the lopsided regional distribution of the brunt. New York City accounts for fully ii-thirds of the local cost, and poorer upstate areas pay proportionally more than the wealthier downstate suburbs. A comprehensive solution would necessarily skew in the contrary direction, with New York City residents reaping most of the benefit, and downstate suburban taxpayers taking a fiscal hit.

In the past ii years, county leaders' perennial call to be relieved from Medicaid costs has gained new momentum. State takeover plans have been put forward by members of Congress, country legislators and at least two candidates for governor. Nevertheless, these proposals either exclude New York Metropolis or offer it only partial relief—which would be hard to justify as a matter of fairness—and none fully addresses the question of financing.

This issue brief explores the financial considerations and policy challenges associated with eliminating the local Medicaid share and reviews the major options for implementing a state takeover.

Regardless of how approached, such a takeover would correspond a major change in a program affecting the lives and livelihoods of millions of New Yorkers. The cost and complexity of the task should not be underestimated, and all options would crave difficult trade-offs.

Background

Medicaid is a government-run wellness plan for the poor and disabled that is managed by states under federal guidelines, and was significantly expanded as office of the Affordable Intendance Human activity. New York's version is 1 of the largest, nearly generous and costliest Medicaid programs in the country. Information technology currently covers more 6 million New Yorkers, or almost one-third of the population, with a total budget for fiscal year 2019 of $70 billion.

The program is financed with a mix of federal and state-based coin, with the federal share varying co-ordinate to a state's per capita income. In New York, Washington pays a scrap more than than one-half of overall costs.

States also have the option of shifting costs to local regime, which New York does more than any other. This policy dates back to the program'due south inauguration in 1966, when information technology replaced pre-existing wellness programs that were shared between New York City, the other 57 county governments and the country.5

Local governments originally paid one-half of the non-federal share, or 25 percent of total costs, for medical bills incurred past their low-income or disabled residents. This percentage declined over the years as the state reduced or limited the local share of certain portions of the program.

Starting in 2006, then-Governor George Pataki successfully pushed the Legislature to cap the growth of counties' Medicaid expenses at 3 percent per year, shifting more costs to Albany. In 2012, in a measure avant-garde by Governor Cuomo, lawmakers phased the cap down to 0 percent, freezing the local share every bit of 2015.

The resulting savings have been significant. Had those steps not been taken, the Division of the Budget estimates that local governments would currently exist spending an boosted $3.3 billion per year. The cost-shift back to the land has increased by $ii.3 billion since Cuomo took office in 2011—representing 15 percent of the overall growth of state-funded spending during that fourth dimension.6

The frozen amount at present paid past local governments is $7.6 billion, including $5.3 billion from New York City and $2.three billion from the other 57 counties combined. That amounts to virtually 12 percentage of the total Medicaid budget, a share that gets gradually smaller as overall spending rises.

Touch on on local finances

Even with the freeze, Medicaid remains one of the largest expenses faced by local governments in New York—and 1 they have little or no ways to control. For 2016, information technology represented ix per centum of total expenditures for both New York City and, on average, the other 57 counties' governments.7

This heavy burden falls unevenly across the state—because the toll for each jurisdiction is based not on power to pay, only on historic usage of the plan by local residents.

Hardest striking by near measures is New York City, largely due to its disproportionately large population of Medicaid recipients. (Come across Table one.) Its Medicaid costs are the highest in the country, both on a per-capita footing and as a share of personal income, and fifth highest as a share of property value.

The burden on the other 57 counties varies widely. Per capita Medicaid costs range from $100 in Putnam to $279 in Sullivan. The toll per $one,000 of personal income ranges from $ane.68 in Putnam to $6.83 in Chautauqua. The cost per $i,000 of property value ranges from nineteen cents in thinly populated Hamilton to $5.63 in Montgomery. (See Figure 1 and Appendix 1.)

Figure 1. Local Medicaid Contribution Per Capita

The distribution of Medicaid costs amongst local governments is generally regressive, in that counties with proportionally higher Medicaid payments also tend to take college poverty rates and lower median incomes. (See Effigy ii and Appendix 2.)

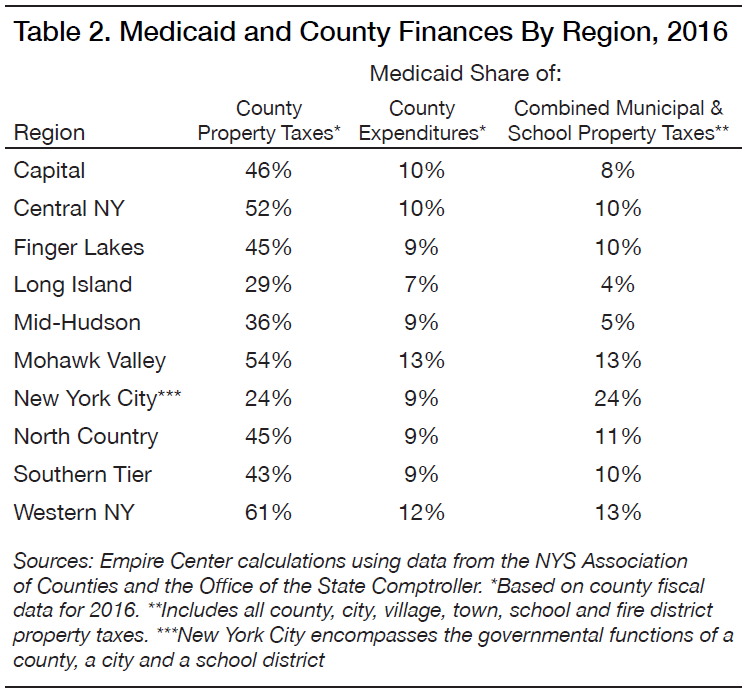

The local share of Medicaid as well contributes to the burden of property taxes, which are a principal source of revenue for counties. Outside New York City, Medicaid costs equate to forty percent of overall county property revenue enhancement revenues. Among private counties, the ratio of Medicaid spending to holding taxation revenue varies widely, ranging from 8 percent in Hamilton to 79 percent in Oneida. (See Table 2 and Appendix iii.)

With sales taxes and other revenues factored in, Medicaid accounts for 9 percent of counties' total spending on boilerplate, ranging from 3 percent in Hamilton to 16 percent in Fulton.

Of course, property owners exterior New York City pay taxes not just to county governments, just as well to schoolhouse districts, cities, towns, villages and fire districts. As a share of total holding-revenue enhancement liability—which is arguably the more relevant comparison—local Medicaid costs average 7 percent outside New York Urban center.

This, as well, varies considerably past canton and region, every bit seen in Table 2 and Appendix iii. Regionally, the share of combined holding taxes devoted to Medicaid ranges from iv pct on Long Isle to 13 per centum for the Mohawk Valley and Western New York. Past county, the share ranges from 2 percent for residents of Hamilton Canton to 17 per centum for residents of Chemung Canton. (Run across Figure 4.)

For New York City, which is both much larger and differently structured than other counties, Medicaid costs equate to 24 percent of holding revenue enhancement revenues, and ix percent of overall revenues.

Past proposals

Calls to eliminate the local share of New York Medicaid date back to its earliest years. One of the showtime came from Governor Nelson Rockefeller in 1967, just one yr subsequently lawmakers launched the program at his urging. Also proposing state takeovers during their terms were Governors Hugh Carey and Mario Cuomo.

Those early plans typically called for some version of a tax swap. In 1994, for instance, Mario Cuomo called for counties to forfeit a portion of their sales revenue enhancement revenue—and for New York City to requite up role of its income revenue enhancement revenue—in return for the state taking over the local Medicaid share. This would have been advantageous for counties at the time, considering Medicaid costs were rise more rapidly than sales revenue enhancement revenue.

"In the first couple of years the swap would exist nearly even," The New York Times wrote in 1994. "But if Medicaid costs continue to explode, the metropolis and counties would eventually come out alee."8

However, Mario Cuomo's plan was non taken upwardly past the Legislature.

The fence over a state takeover was rekindled in 2017 with the election of U.S. Rep. John Faso (R-Columbia County), a erstwhile Associates minority leader, who had campaigned on the issue. In March 2017, Faso and Rep. Chris Collins (R-Erie Canton) cosponsored federal legislation requiring New York to eliminate the local share of Medicaid for counties outside New York City within two years.9 Faso and Collins later added the same provision as an amendment to several GOP bills aimed at repealing and replacing the Affordable Care Act—one of which came within a single vote of passage in Congress.

In March 2018, the Assembly'south minority Republicans unveiled a proposal to eliminate the 57 counties' Medicaid contributions gradually over 10 years, along with one-half of New York City'due south contribution over xx years.x

This programme was part of a broader parcel that called for a mix of spending cuts, spending increases and revenue raisers—the latter including a 50 percent reduction of what are at present $420 one thousand thousand a year in state taxation credits for film and Goggle box production, which are due to expire in 2022, and the elimination of a $1 billion property tax relief credit that is due to dusk at the end of 2019. However, the proposed revenue increases and plan savings would non fully offset the cost of the Medicaid takeover and other spending increases.xi

In May 2018, bulk Republicans in the land Senate introduced and quickly passed two variations of a takeover. The get-go chosen for a five-year phase-out of the local share for counties outside New York City only. The second called for a ten-year phase-out that fully eliminated payments by the 57 counties and partially eliminated New York City'southward share, limiting the city's savings to $2.3 billion. Neither bill included a plan to replace or offset the lost revenue.12

The Senate bills would mandate that local governments dedicate their savings to reducing local taxes, but provide no specifics for how compliance would be divers or enforced.

Although recent proposals have been advanced by Republicans, there is some bipartisan support for the underlying goal. Assemblywoman Crystal Peoples-Stokes (D-Buffalo) is lead sponsor of a bill that would phase out the local share of Medicaid over a five-yr catamenia. Originally introduced in 2011, the neb is currently cosponsored by a young man Democrat, Phil Steck of Albany County, along with Republicans Joseph Giglio of Cattaraugus County and Andrew Goodell of Chautauqua County.13

A state takeover of local Medicaid costs has also been advocated by ii gubernatorial candidates: Dutchess County Executive Marcus Molinaro, a Republican, and erstwhile Syracuse Mayor Stephanie Miner, a Democrat seeking to run as an independent. Every bit of early July, neither had released a detailed programme.

The primary goal of all such proposals is property revenue enhancement relief. A full land takeover would equate to a 24 percent reduction in belongings taxes imposed by New York Urban center, and an average 40 percent reduction in county taxes elsewhere in the land. As discussed, however, the potential relief every bit a share of full property taxes outside New York City would average a relatively modest 7 percent—lower in downstate suburbs, higher in upstate counties.

Policy options

As it at present stands, the local share of Medicaid is an unfunded mandate that imposes disproportionate costs on poorer jurisdictions while contributing to New York's loftier local tax rates beyond the lath. It'southward unlikely that state lawmakers would approve such a system if they were designing the plan from scratch.

Worthy as it is, yet, the goal of eliminating the local share is expensive and must compete with other priorities. If Albany had an actress $8 billion per year to spend, it'southward not clear that local taxation relief should take precedence over, say, an investment in infrastructure.

Assuming the state does commit to a takeover, it should take care to exercise and so in way that does not create equally problematic tax burdens and inequities somewhere else.

A review of the major policy options follows:

Excluding New York City

I strategy for reducing the cost of a takeover would be to limit is applicability to New York City, which accounts for 70 per centum of local spending on Medicaid.

The Associates minority's program would eliminate only half of the city's contribution, and do so over twice every bit long a flow as for other counties. One of the 2 bills passed by the Senate would phase out $2.three billion of the city'due south share, which is less than half of its $five.three billion tab. The second Senate pecker would omit the city entirely, as would the Collins-Faso subpoena in Washington.

While this would expediently reduce the cost of a takeover, excluding New York City would be hard to justify on policy grounds.

Creating such an exception would arbitrarily limit or deny relief to the grouping of local taxpayers shouldering by far the heaviest toll. Plus, information technology would put urban center residents (and a large number of Connecticut and New Bailiwick of jersey commuters with jobs in the metropolis) in the position of subsidizing relief for others, because they pay a disproportionately large share of the state taxes redistributed from Albany.

The effect would be to make the state'due south Medicaid financing system more inequitable than it already is.

A more than constructive way to limit cost would be to provide partial relief to all jurisdictions based on demand. For case, the country could commit to take over the portion of each canton's contribution that exceeds a certain share of its residents' incomes, or of the local property value.

Under whatever such scenario, still, New York Urban center would likely receive the bulk of the

benefit.

Swapping for a share of sales tax

1 takeover approach that has been floated repeatedly in the by—past Mario Cuomo and others—would take the form of a sales tax "bandy": The land would presume responsibility for the counties' share of Medicaid costs in return for counties giving up a portion of their acquirement from sales taxes.

This has the potential advantage of spreading costs less regressively—at to the lowest degree among counties outside New York Urban center.

Table 3 and Appendix 4 bear witness the effects of two revenue enhancement swap scenarios.

The beginning assumes that New York City would be excluded. To outset the Medicaid payments of the other 57 counties, the state would demand to divert 1.2 pct points of the counties' taxable sales. Counties with relatively more than Medicaid recipients and less retail business—mostly upstate—would generally relieve money, at least in the short term. The mid-Hudson suburbs and Long Isle, with relatively few Medicaid recipients and stronger retail economies, would pay more.

Under the second scenario, which includes New York City, the share of sales tax necessary to finance the swap would ascension to ii.2 percentage points. The city would reap the vast bulk of savings and virtually other counties would feel a net loss.

A swap fabricated more sense years ago, when counties' Medicaid costs were typically growing faster than sales tax revenue—meaning the trade virtually certainly would have saved

coin for all counties in the long run.

Now that the local share is frozen, still, the dynamic has reversed. Sales taxes generally ascension and local Medicaid costs are stock-still, meaning a swap would eventually go out all counties worse off than before.

Increasing state taxes

Fifty-fifty in the context of a $170 billion all-funds state budget, finding another $7.six billion in revenue would be no small matter.

The toll of a total takeover would equate to a 15 percentage hike in the state's personal income tax, which is projected to bring in $50 billion in fiscal twelvemonth 2019.14

The country's total taxation collections—including levies on personal income, business income, retail sales, cigarettes and gasoline—are projected to be $78 billion.fifteen The price of a takeover equates to an beyond-the-board increment in all of those taxes of almost 10 percent.

The acquirement needed to finance a takeover would be much more the amount to exist raised past other country revenue enhancement hikes currently on the table. The Assembly Democrats' proposed hike on New Yorkers with incomes of $five million or more—earmarked for spending on schools and health care—would heighten $five.vi billion, or three-quarters of the amount necessary for a takeover.sixteen Mayor Nib de Blasio's proposed tax on the wealthy, intended to finance repairs to the subway system, would raise $one billion or less.17

Financing a takeover through the state income tax would shift the tax burden rather than reducing information technology. Poorer parts of the state would generally pay less, while richer areas would pay more. (See Table 4 and Appendix v.) One group that clearly stands to lose is out-of-state commuters, who would become from contributing nothing toward Medicaid's local share as of at present, to conveying 17 percent of the toll post-takeover.

Assuming the increment is weighted toward college income groups—equally such proposals usually are—this approach would farther increment the state's heavy reliance on acquirement from high earners, and from the financial sector in detail. This would heighten the state's fiscal vulnerability to volatility on Wall Street and the broader economy.

Any motility in this direction would likewise aggravate New York'due south status as a high-tax country. The enactment of federal revenue enhancement changes last twelvemonth—which capped the deductibility of land and local tax payments—effectively increased the marginal cost of residing in New York compared to states with lower taxes. The net combined state-and-metropolis income revenue enhancement rate on New York City'due south highest earners has jumped to virtually 13 per centum, its highest level ever, and 2d only to California among the fifty states.

In this context, whatsoever significant income tax hike would further damage New York's economic competitiveness and undermine the benefit of tax relief at the local level.

Especially counterproductive would be any increase in taxes on health care itself. The state already raises $iv.5 billion per year from taxes on health insurance.xviii A takeover that excludes New York City would entail a 51 percentage increase in these surcharges, which are already among the largest levied by any state. A statewide takeover would require an increase of 169 percent.

This approach would further bulldoze up the cost of health insurance for New Yorkers, who already pay some of the highest premiums in the U.S. This would cause more than people lose or drib coverage and ultimately drive up Medicaid enrollment and costs.

Cutting state spending

While there is certainly waste matter in the state budget, financing a Medicaid takeover through spending reductions would require much more than belt-tightening.

The price tag for a takeover, at $7.vi billion, equates to 8 percent of all spending funded by land taxes. Information technology's more than the entire budgets for major functions such as parks and the surroundings ($1.6 billion), economical evolution ($2.1 billion), mental health ($2.ix billion), prisons ($3 billion), the land-funded portions of transportation ($five billion) and the Country Academy of New York ($seven.2 billion).19

Realistically, a cost-cutting attempt on this scale would take to consider the two largest items in the state budget: school aid and Medicaid itself.

A takeover could hypothetically be funded past a 29 percent cut in school assistance. But that would likely backlash if local districts responded past raising their property taxes, which are much costlier for most homeowners than county taxes.

The most logical identify to look for cuts would exist Medicaid, both because it is the original source of the counties' expense, and considering New York'due south program is so expensive. Its per capita toll in 2015 was $3,054, the highest of any state and 76 percentage above the national average.20

Finding sufficient savings from the program would be complicated by the federal aid formula, which matches state and local spending on a roughly dollar-for-dollar basis. As a upshot, the state would have to cut overall Medicaid spending by $15 billion—or 22 percent—to achieve net savings of $7.6 billion for itself.

Even after a 22 per centum cutting, however, New York would still rank among the pinnacle 10 states in terms of per capita Medicaid spending.

Cutting the Medicaid upkeep

The least painful style to cutting Medicaid spending would exist rooting out waste, fraud and abuse—which certainly remains a significant cistron in New York's programme. To cite ane instance, a recent audit by the office of land Comptroller Thomas DiNapoli found that the Health Section spent $one.3 billion over six years on Medicaid managed care premiums for recipients who already had other health insurance.21

Another desirable approach would exist improving the efficiency of care delivery—for instance, by encouraging patients to use clinics and urgent-intendance centers instead of emergency rooms for not-emergency issues, or improve managing chronic illnesses such every bit diabetes and asthma to avoid hospitalizations. If successful, these steps would have the added benefit of improving outcomes for recipients.

However, the state already devotes considerable resources to eliminating waste through the comptroller's office, the Wellness Department, the Office of the Medicaid Inspector General and various law enforcement agencies.

The state is too currently improving efficiency past enrolling most recipients in managed care plans and increasing coordination among providers through the Commitment System Reform Incentive Payment plan.

Given those existing efforts, it's unlikely that additional anti-fraud and efficiency efforts, by themselves, would generate $15 billion in savings in the short term.

To quickly lower spending past 22 percent, the state would have to consider more politically difficult steps, such as cutting fees to providers, trimming benefits for recipients or reducing enrollment. Each of those steps comes with drawbacks.

Medicaid fees are generally lower than those paid past Medicare and commercial insurance, and many providers report losing money when they care for Medicaid recipients. Amidst other consequences, this discourages doctors from participating in the plan and strains the finances of hospitals who serve the needy, potentially compromising the quality of care for all patients. A farther significant reduction in fees would aggravate all of these issues.

Another cost-cutting option would be trimming the benefits that Medicaid provides, some of which are optional under federal law. Theoretically, for example, New York could finish Medicaid coverage for adult dental care, eyeglasses, hospice care, prosthetics or even prescription drugs.22

Such steps would bear upon the range of Medicaid recipients, from low-income able-bodied adults to severely disabled children and frail residents of nursing homes. Many would have no other way of paying for the services, and their health and quality of life might be compromised equally a outcome.

Eliminating even major benefits would not necessarily generate sufficient savings. For instance, Medicaid's total prescription drug spending for 2016 was $3.3 billion, less than a quarter of the amount necessary to finance a takeover.23

A third approach to cutting Medicaid costs would be reducing enrollment. New York'southward unusually expansive programme covers 6.1 million people, or a 3rd of the population, which every bit of 2015 was the second-highest share of any state afterwards New Mexico.24

The country could potentially trim the rolls past, for example, restricting eligibility for the "medically needy," who live above the poverty line merely have medical or nursing-home bills that exceed their income.

This would come at the cost of allowing more New Yorkers—especially the elderly, disabled and seriously ill—to be impoverished by medical expenses. Information technology would also exist hard politically: For 28 years in a row, governors of both parties accept proposed ending "spousal refusal"—a legal strategy that allows long-term care patients to qualify for Medicaid while protecting the income and avails of their spouses—and they were turned downwardly past the Legislature every time.25

Strengthening the Medicaid 'global cap'

The claiming of eliminating counties' Medicaid costs becomes more manageable if the change can be phased in over a menses of ten to 20 years. This opens the door to an existing price-cutting strategy with a tape of success: the "global cap" on Medicaid spending growth.

If the existing cap were broadened and strengthened, it could potentially generate enough savings to finance a gradual takeover.

The electric current cap was enacted in 2011 every bit part of Governor Andrew Cuomo's offset budget. Information technology limited year-to-year growth of country Medicaid spending to the 10-yr rolling average of the medical inflation charge per unit.26

To detect the necessary savings, the governor empaneled a Medicaid Redesign Team representing various stakeholders in the health-care system. If the team'due south efforts savage short, the health commissioner was empowered to cut Medicaid fees every bit necessary to run across the cap.

This system largely worked every bit intended, especially in its early years.

Under Medicaid director Jason Helgerson, the Redesign Team advanced dozens of reform ideas intended non just to save coin, only also to improve intendance and augment access. Maybe most importantly, the state enrolled a far greater share of Medicaid recipients into managed care plans, including groups that had previously been exempt, such every bit the mentally ill and nursing home residents.

Meanwhile, state Medicaid outlays stayed at or below the global cap, even as enrollment surged with enactment of the Affordable Intendance Human action. Per-recipient spending dropped significantly—from $12,000 in 2011 to $9,700 in 2015—and measures of care quality generally held steady or improved.27

Over time, however, weaknesses in the global cap became apparent. It restrained spending on the bulk of the program, known as Department of Health (DOH) Medicaid, simply did not comprehend services provided through the Office of Mental Health, the Office for People with Developmental Disabilities or the Office of Alcoholism and Substance Abuse Services. Certain expenses were also exempted, such as labor costs associated with a Cuomo-sponsored hike in the minimum wage.

As of 2017, the cap governed 97 percentage of DOH Medicaid. That dropped to 93 percentage for 2019, and is projected to fall to 88 percent past 2022.28

Meanwhile, enrollment leveled off, rendering the cap significantly less restrictive. Per-recipient spending climbed dorsum to more than $11,000.

The outcome of these trends is that overall state spending on Medicaid is growing essentially faster than the medical inflation rate. The state's latest financial plan shows increases of 4.2 pct in the current fiscal year, half dozen.three percent for 2020, five.4 percent for 2021 and 4.2 percent for 2022—whereas medical inflation is projected to go on at well-nigh 3.ane percent.29

If the growth charge per unit could be lowered past 1.4 points—the difference betwixt medical aggrandizement and the current trend—the almanac savings would be substantial. As shown in Figure three, they would reach $1.2 billion by fiscal twelvemonth 2022, and $viii.ii billion—enough to eliminate the local share—by 2034.

To achieve those savings, the global cap could exist strengthened in ii ways:

First, information technology could be expanded to cover all Medicaid spending, including the portions managed by OMH, OPWDD and OASAS and minimum wage-related costs for all providers.

2nd, the global cap should be supplemented with a per-recipient cap, to protect against excessive spending growth when enrollment is flat or failing.

State officials would withal face the hard work of removing waste and improving efficiency and, possibly, the hard choices to cut fees, benefits or enrollment. Simply they could do so gradually and advisedly, without sudden or severe changes.

Local taxation relief

If the goal of a state takeover is belongings tax relief—equally opposed to giving local officials more than money to spend—the country will need to set guidelines for how the savings are used.

A readily available mechanism is the state's belongings tax cap.* Enacted in 2011, this law limits the twelvemonth-to-year growth of each jurisdiction's property tax collections to two percent or the inflation rate, whichever is less. The cap applies to the total corporeality to be raised by property taxes, known as the "levy," with certain limited exceptions.

The cap can be overridden only with approval by a 60 per centum majority of the decision-making trunk—which, for counties, would be a legislature or board of supervisors. The constabulary does not currently use to New York City.

In enacting a takeover programme, the state could require that the annual savings accruing to each county be subtracted from its electric current levy before computing the capped amount for the adjacent year.

Take, for instance, a hypothetical county with a belongings tax levy of $100 one thousand thousand and Medicaid takeover savings of $v million. Every bit things stand now, it would be allowed to increase the levy by as much $2 million, to enhance a full of $102 million in the following year—plus spend the $5 million as it wished.

Under a modified cap, the county'due south electric current levy would be reduced past the $v one thousand thousand in savings, to $95 million. The county would then be allowed to increase taxes by no more than than ii percent of that reduced base, or $1.9 one thousand thousand, for total collections of $96.ix million in the ensuing twelvemonth. Instead of increasing by $2 1000000, tax collections would decrease by $3.i one thousand thousand.

Under this plan, a county would have the flexibility to override the cap, but only with 60 per centum blessing by its legislature in a separate vote preceded by a public hearing. This would put the public on detect of the decision and encourage local officials to prioritize tax relief.

The tax cap, as modified, could be expanded to include New York City—requiring the City Council to articulate at least one boosted hurdle earlier adding to the city'southward already enormous taxation burden.

Using the savings to reduce the city's income tax—as contemplated in one of the Senate GOP proposals—would exist more than complicated. While holding revenue enhancement rates are controlled by the City Council, changing urban center income tax rates would crave further action by the state Legislature.

Determination

The local share of Medicaid has evolved into something that's hard to defend, but too hard to unwind. Eliminating it entails either the reallocation of nearly $8 billion in state resource, or $fifteen billion in cuts to a programme that pays medical bills for one in three New Yorkers and serves equally a financial mainstay of the state's entire health care system.

Because the current organisation distributes costs so unevenly, any solution must therefore distribute relief unevenly. Including New York Metropolis more than triples the cost, from $2.3 billion to $7.six billion, just excluding it would be manifestly unfair and politically impractical.

The most plausible approach is to slowly phase out the local share over a period of 10 years or more, and make up for the lost revenue with savings squeezed from the Medicaid program itself—which, despite efficiency improvements, remains much costlier than national norms. The state effectively began that process more than a decade ago, when it capped and so froze local payments, causing them to gradually shrink in real terms due to the furnishings of inflation.

Committing to full elimination, however, would be a major escalation, both in dollars and in difficulty. Leaders committing to this path must be prepared to grapple with tough choices for years to come.

Click here for the full report, with appendices.

Measured equally a percent of combined county, municipal and school property taxes, the local share of Medicaid costs adds the about to property tax burdens in upstate counties with large low-income populations, the more darkly shaded areas above. Medicaid has the to the lowest degree affect on total property taxes in affluent suburban counties on Long Isle and in the Hudson Valley, which are lightly shaded. Two outliers at opposite extremes: New York City, whose Medicaid share equates to nearly one-quarter of property taxes, and Hamilton County in the North Country, which has a tiny year-round population and

low Medicaid property revenue enhancement impact. Meet Appendix Table 3 for detailed county percentages.

ENDNOTES

- National Association of Counties, "Medicaid and Counties: Understanding the program and why information technology matters to counties," January 2017, http://world wide web.naco.org/sites/default/files/documents/NACo-Medicaid-Presentation-updated%201.26.17.pdf.

- Data provided to the author past the New York Country Association of Counties.

- Data provided to the author by the New York State Division of the Budget.

- Op. cit., NYS Association of Counties.

- Citizens Budget Commission, "A Poor Mode to Pay for Medicaid: Why New York Should Eliminate Local Funding for Medicaid," December 2011, https://cbcny.org/sites/default/files/media/files/A%20Poor%20Way%20to%20Pay%20for%20Medicaid.pdf.

- Op. cit., Segmentation of the Upkeep.

- Based on county revenue and spending figures for 2016 obtained from OpenBookNewYork.com, operated past the New York Country Role of the Country Comptroller.

- "Mr. Cuomo'south Medicaid Cure," The New York Times, February 18, 1994. https://www.nytimes.com/1994/02/eighteen/opinion/mr-cuomo-s-medicaid-cure.html.

- Jesse McKinley, "Medicaid Fight Lands in New York, Crossing Party Lines," The New York Times, March 21, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/21/nyregion/health-intendance-medicaidnew-

york-collins.html?_r=0. - "Addressing the Medicaid Mandate," posted on Medium.com by the New York State Assembly Republican Conference, March 12, 2018, https://medium.com/@NYS_AM/addressing-the-medicaid-

mandate-362882036e90. - "Our Vision for New York: Structural Changes for a Stronger State," Assembly Republican Conference (PowerPoint presentation), April 17, 2018.

- Senate Bills 8411 and 8412 of 2018.

- Associates Nib 2236 of 2018.

- FY 2019 Updated Financial Programme, New York Land Segmentation of the Budget, May 2108, p. 73, https://www.budget.ny.gov/pubs/archive/fy19/enac/fy19enacFP.pdf.

- Ibid.

- Eastward.J. McMahon, "Heastie'due south gazillionaire tax," New York Torch, January 26, 2017, https://www.empirecenter.org/publications/heasties-gazillionaire-taxation/.

- Emma Thou. Fitzsimmons, "Bill de Blasio Will Push for Tax on Wealthy to Prepare Subway," The New York Times, Baronial 6, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/06/nyregion/bill-de-blasio-will-button-

for-taxation-on-wealthy-to-fix-subway.html. - Op. cit., FY 2019 Updated Financial Plan, p. 106.

- Budget numbers for FY 2019 obtained from SeeThroughNY.cyberspace, operated by the Empire Center, https://www.seethroughny.net/nysbudget/disbursements/.

- Calculations by the author based on data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and the Census Bureau, https://www.empirecenter.org/publications/medicaid-chip-spending-bystate/.

- Inspect Report 2016-S-threescore, Office of the State Comptroller, June 2018, http://www.osc.land.ny.us/audits/allaudits/093018/sga-2018-16s60.pdf.

- Listing of mandatory and optional Medicaid benefits at Medicaid.gov, https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/benefits/list-of-benefits/index.html.

- Bill Hammond, "The Toll of Cures," Empire Center, April 10, 2018, https://www.empirecenter.org/publications/the-toll-of-cures/.

- Calculations by the author based on information from CMS and the Census Bureau, https://www.empirecenter.org/publications/medicaid-fleck-enrollment-vs-poverty-rate-by-state/.

- Dan Goldberg, "28th time'southward the charm," Political leader New York, January 18, 2018, https://world wide web.politico.com/states/new-york/newsletters/pol-new-york-health-care/2018/01/18/28th-times-the-charm-025437.

- "Governor Cuomo Announces On-Time Passage of Historic, Transformational 2011-12 New York Country Budget," press release from the governor's office, March 31, 2011, https://www.governor.ny.gov/news/governor-cuomo-announces-time-passage-historic-transformational-2011-12-new-york-country-budget.

- Per-recipient spending figures based on calculations by the author. For more on the track record of the Medicaid Redesign Squad, come across also, "What Ails Medicaid in New York: And Does the Medicaid Redesign Team Take a Cure?" Citizens Upkeep Committee, May 2016 (https://cbcny.org/sites/default/files/media/files/REPORT_MEDICAID_05232016_1_0.pdf), and "Medicaid in New York: The Continuing Challenge to Better Intendance and Command Costs," Office of the Country Comptroller, March 2015 (http://osc.state.ny.us/reports/wellness/medicaid_2015.pdf#search=%20medicaid).

- Op. cit., FY 2019 Update Financial Plan, pp. 99-101.

- Ibid.

Source: https://www.empirecenter.org/publications/shifting-shares/

Posted by: gunndentoory1961.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Much Money Does Nys Give Its Counties"

Post a Comment